The Pantheon is Rome's pre-eminent architectural survivor. Built in the second century CE as a temple to all the gods, it is today the best-preserved of all monumental Roman buildings, not just in Rome but anywhere . . .

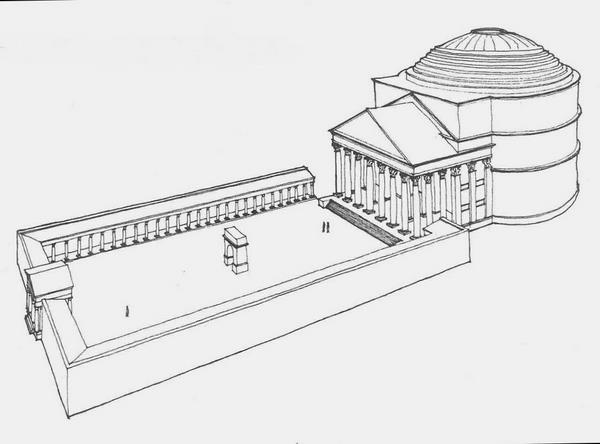

Today the Pantheon occupies an entire block to itself, but originally its relation to the surrounding cityscape was more complicated. Modern research suggests that in ancient times the forecourt piazza was enclosed by a low-roofed colonnade . . .

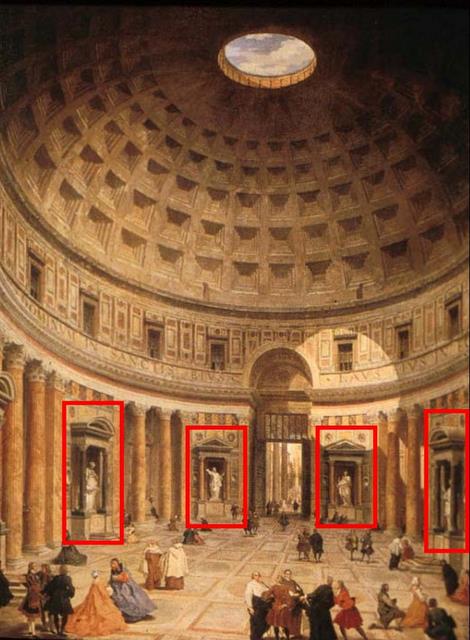

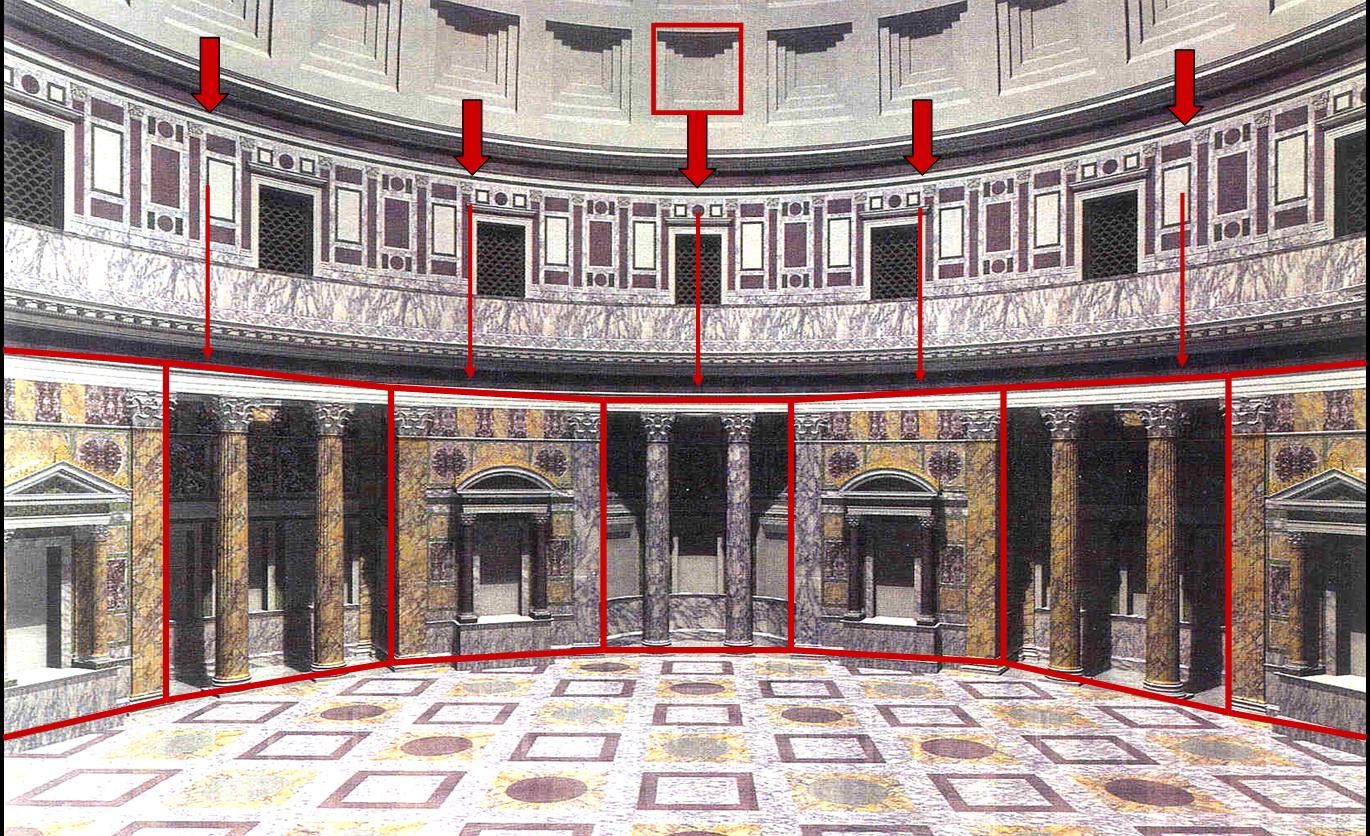

. . . Those huge bronze doors are still intact, and the interior beyond them belies all Greek expectations. Far larger than the entrance portico implies, expansively circular rather than narrowly rectangular in form, capped by a vast floating dome instead of a flat ceiling, amply lit by light streaming in through the oculus at the dome's peak, elaborately decorated with colored marbles, granites, and Imperial porphyry: this is a space that leaves he time-honored conventions of Greek temple architecture far behind . . .

. . . The presence of the gods here has been relegated to the periphery – inside the series of chapel-like openings and statue-framing aedicules that are alternatively carved out of and set against the circular wall – and the center of the interior is conspicuously, dramatically empty.

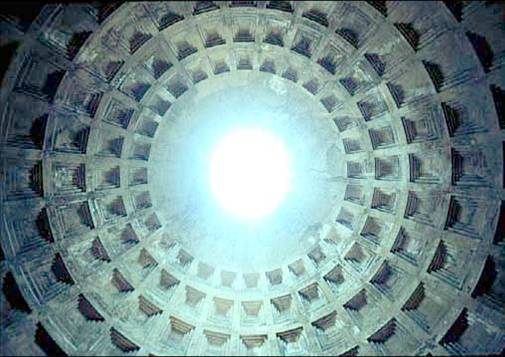

Empty, that is, of statuary. But not empty of light . . .

. . . When the Pantheon is first entered, then, the absence of a central statue and the presence of light streaming in through the oculus forces attention inexorably on the interior's most dramatic architectural feature: the dome.

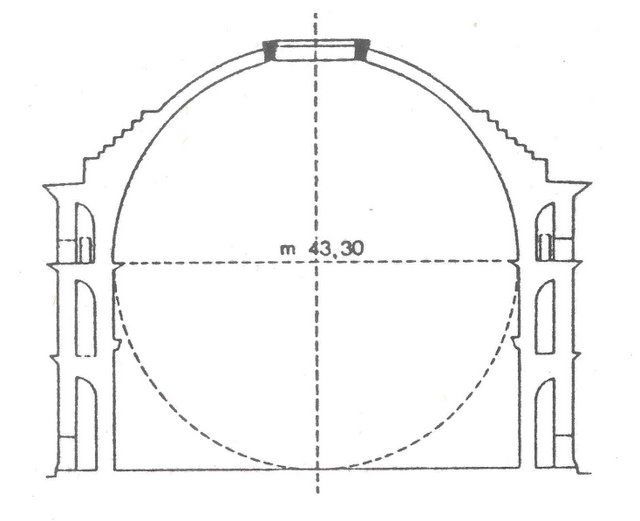

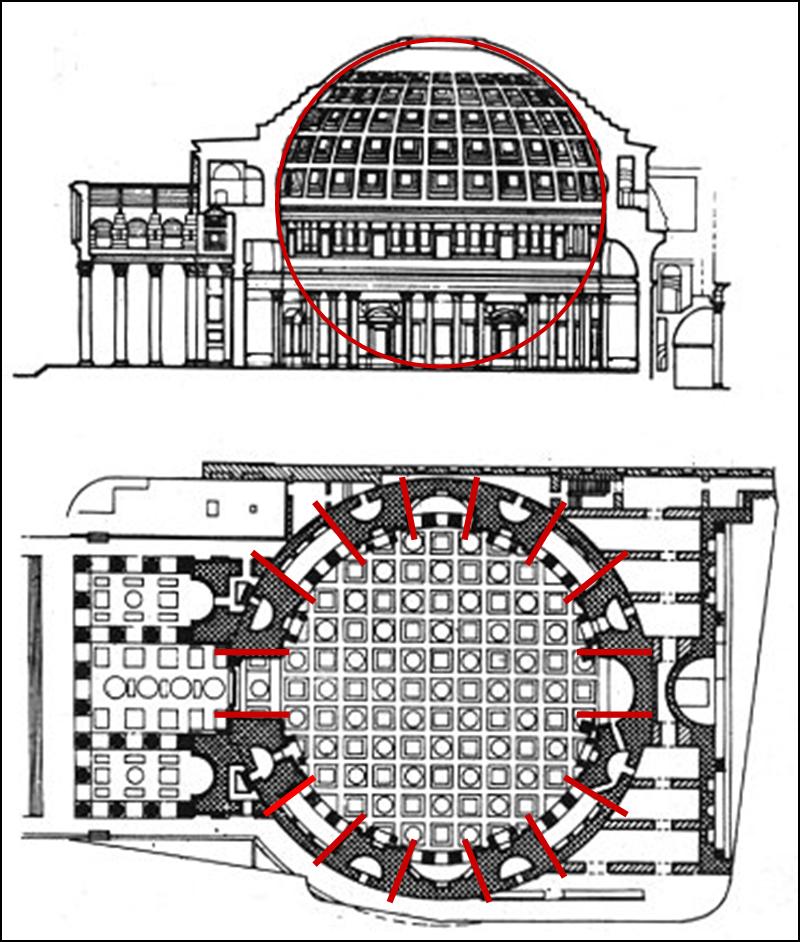

The temple's architect – his identity is not known, though Hadrian himself may have had more than a passing hand in the building's overall design – shaped the dome with extraordinary precision. It is a perfect half sphere, and if the half sphere were extended downward, the full sphere would just touch the floor of the interior exactly at its center.

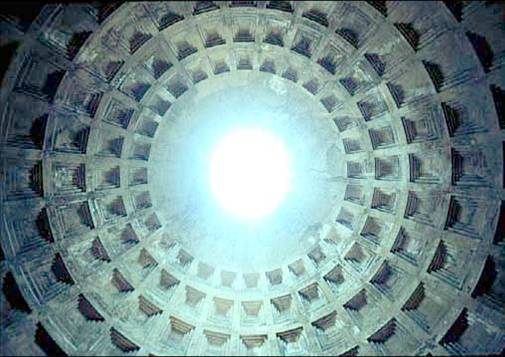

The lower two-thirds of the dome is inset with five rings of coffers, each coffer consisting of four receding levels of squares that are nested off-center (that is, scrunched together toward the upper edge of each coffer). The visual effect of this purposefully skewed coffer design, when combined with the overall decrease in size of the coffers as they move up the dome, is one of the ever-increasing intensity . . .

Inevitably and powerfully, the great dome calls to mind the far greater vault of the heavens outside. The parallel would have been even more forceful in ancient times . . .

With the fall of the Roman Empire, the Pantheon lost forever its aura of political and civic importance. But a thousand years later it emerged from the Middle Ages with its architectural importance intact . . .

. . . As a thousand-year-old Christian church, the Pantheon was for Renaissance builders an architectural textbook uniquely preserved by God, a holy writ in which they could find the rules by which they might create an architecture that would equal and perhaps even surpass the ruined architecture of the ancients.

Foremost among those rules was the Pantheon's mathematically elegant geometry . . .

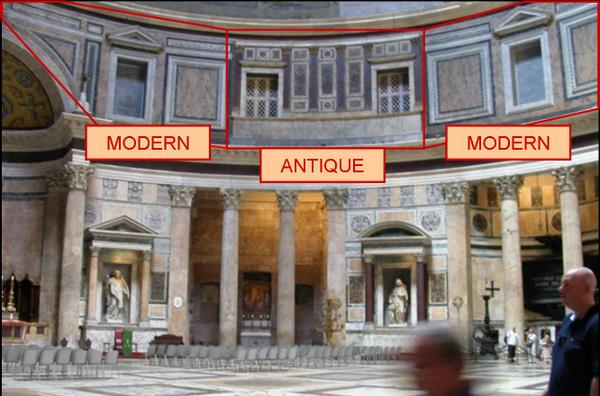

One feature of the interior, however, does not relate obviously to the overall geometric scheme and is much discussed among architects and scholars even today . . .

It was probably this discrepancy that produced the only major change in the Pantheon's interior since antiquity. In the 1740s, the entire attic section of the wall – the upper story, below the dome – was redesigned . . .

. . . From a strictly geometric point of view, the change is understandable (if historically regrettable). But it begs the fundamental question: Why does the original design, otherwise so precisely and perfectly ordered, fail to align its upper and lower elements? The answer can only be a matter of speculation, but it is entirely possible – even probable – that the discontinuity was carefully planned . . .

Today the Pantheon is much reduced in function (although it is still a consecrated church). But as an architectural memorial to the ancient Romans it remains incomparable, and its influence on Western architecture since the Renaissance can scarcely be overstated . . .